Corolla, NC – An Overview

The place names of this area reflect the early Native American heritage. Currituck is a derivation of a Native American word meaning “land of the wild goose.”

Chowanog, Poteskeet, Pamunkey and other tribes that lived on the mainland used the barrier island as fishing and hunting grounds and named it for its abundance of geese. Europeans, who began settling in the area in the 1600s, applied the word to the barrier island, the county, the sound and two inlets.

In the late 1600s and early 1700s, a few European settlers resided on the northern barrier islands, but most people preferred to live on the mainland. Until the early 1800s, Currituck Banks was separated from Virginia by Old and New Currituck inlets and from Duck by Caffeys Inlet, so getting there was only possible by boat.

By the mid-1800s there were several communities, tiny hamlets really, dotting the northern banks. There was Wash Woods nearest to the Virginia line, Seagull a little farther down near Penny’s Hill, Jones’s Hill, a.k.a. Whaleshead or Currituck Beach (now Corolla, NC), and Poyners Hill between Corolla and Duck. The communities were isolated and remote, set amidst the marshes and sands of the barrier islands.

Corolla Was Known for Hunting and Fishing

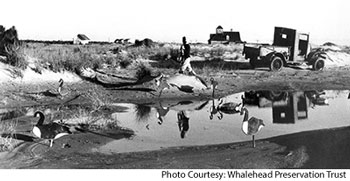

The early residents of the banks fished and hunted to make a modest living. There were even reports of whalers here. They tended gardens and raised livestock, which ran at large on the barrier island. The bankers patrolled the beach to salvage items that washed ashore from numerous shipwrecks, and they recycled many of their goods in creative ways because supplies were hard to get. They traveled by boat to the mainland to sell waterfowl or fish, to purchase supplies or to visit friends and family. The locals also found work guiding and helping wealthy sportsmen from the North who hunted on the Currituck Sound.

In 1892, a writer from Harpers Weekly wrote about the Currituck Banks, “If there were any spot on earth that one would expect to find untenanted, it surely would be this stretch of sand between ocean and sound.… Yet there is a hardy race who have lived here from father to son for over a century. They exist entirely by hunting, fishing, rearing cattle and acting as guides.”

Of these villages, the only one that stood the test of time was Corolla, NC. Other villages petered out as times got hard, but a few residents always hung in there at Corolla. The village was able to thrive partly because of its abundance of government jobs, which offered steady pay. In 1873, when the village was still known as Jones’s Hill, construction began on the Currituck Beach Lighthouse. The red-brick lighthouse, which towered over the small village and the banks, was completed and lit on December 1, 1875. The light keepers and their families added several new residents to the village.

Growth Comes to Corolla, NC

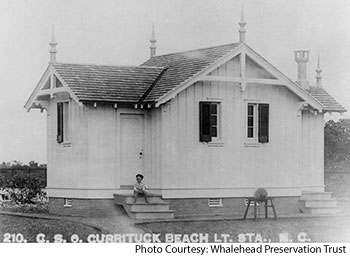

In 1874 the U.S. Life Saving Service established the Jones’s Hill Life Saving Station just east of the Currituck Beach Lighthouse site. This station, which was moved south and later known as Currituck Beach Life Saving Station, was one of the seven original life saving stations on the Outer Banks. Seven local men were hired to staff the station from December through March. The keeper in charge received a salary of $200 a year, while the six surfmen were paid $40 a month for four months, with an additional $3 for every wreck they attended. The surfmen lived at the station, while some of their families resided in the village.

By 1895 Jones’s Hill was busy enough to have its own post office. The postal service, notorious for changing the traditional names of remote villages, required that the villagers send in several suggestions for an official name. The story goes that they submitted Jones’s Hill and Currituck Beach and were looking for other suggestions when someone mentioned that the inner part of a flower is called a corolla. That name was submitted and chosen by the postal service, forever changing the name of the small village.

Corolla’s population was large enough to require a church and schoolhouse. The children of the village had been attending various small schools, but around 1905 Currituck County was ready to support the one-room local school. The county provided a teacher, schoolbooks and standardized grading, and all the children of all grades attended the school together.

Whalehead Is Built in Corolla, NC

In 1922 another work opportunity arrived in the village when Edward and Marie-Louise LeBel Knight began work on Corolla Island (now Whalehead). When the massive house on the sound was finished in 1925, it must have been quite a sight to the modest-living locals. The residence provided many work opportunities, as the Knights employed local men as caretakers and hunting guides to accompany them and their invited guests.

In the 1930s it is said that more than 100 people lived at the village of Corolla, NC. The Depression hit hard in the rest of the country, but on the banks people were able to survive off the wealth of the land and sea. During the period after the Depression, CCC and WPA boys were hired all along the banks to construct the high dunes and plant stabilizing grasses along the oceanfront and to improve the roads in the villages.

By 1940 the Knights had passed away and the “Corolla Island” house was owned by Ray T. Adams, who renamed it the Whalehead Club. During World War II Adams leased the Whalehead Club to the U.S. Coast Guard, which used the house and grounds as a base for its mounted beach patrols. The Coast Guardsmen patrolled the beach looking for enemy soldiers coming ashore or shipwrecks along the coast. German U-boats came very close to the shoreline of the Outer Banks, and locals were required to darken their windows and use no headlights when driving on the beach. The Coast Guard also used the Whalehead Club as a holding station for Coast Guardsmen waiting for assignment after basic training. The village bustled with the influx of servicemen; the church services were full and the post office and store were always busy.

A Slow Down in Corolla, NC

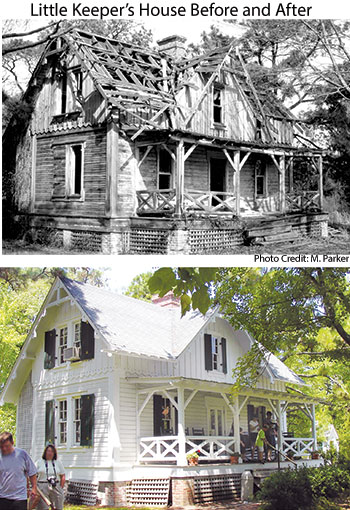

After the war, the population of Corolla, NC, dwindled rapidly. Many residents left the banks to look for jobs on the mainland. The lighthouse, electrified in 1939, no longer required several keepers, just a caretaker. (The villagers, however, didn’t get electricity until 1955.) In the late 1950s Corolla’s population reached its lowest point. The school closed for lack of students, and there were only a few families residing in the village. The church sat empty. The Whalehead Club was empty most of the year, though it was used as a boys’ school, Corolla Academy, in the summers. Later the Whalehead Club was converted into the headquarters for Atlantic Research, a rocket-fuel testing facility.

In the 1970s only about 15 people lived in the village. People who visited or lived there back then say that Corolla felt like the absolute end of the earth. The road leading to Corolla was just an unpaved trail along the soundside, with “truck-swallowing holes” and sugar-fine sand that was nearly impossible to drive through. The Whalehead Club and lighthouse buildings were in grave disrepair. Corolla, NC, was wild and rugged. It was the last coastal getaway of the grandest kind, and anyone who ever went there fell in love with it just exactly like it was.

By the 1970s alternative vacationers were beginning to discover the isolated beaches of the Currituck Banks. Since there were no paved roads leading into Corolla, people drove on the beach from Virginia or Duck. But in 1974, U.S. Fish and Wildlife blocked the Virginia border to prevent excessive traffic in its Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge. Corolla residents were given special passes to be able to go through the gate. The border is still closed today.

And Then a Massive Upturn in Corolla, NC

Meanwhile, developers were buying up sizeable chunks of the Currituck Outer Banks. Ocean Sands and Whalehead were the first large-scale developments on the banks north of Duck. To keep people out of the private developments, the developers constructed a guard gate at the south end of the road that led up the banks. The guard was not allowed to let anyone but property owners past the gate. This was a huge point of contingency for longtime Corolla, NC, landowners who felt locked out of their own land. Sightseers were turned away, but many of them circumnavigated the guard gate by driving up on the beach.

The southern guard gate didn’t come down until October 1984, when the state took over the road and made it part of N.C. Highway 12. The state extended the road to pass through Corolla. With the road open to the public, interest in real estate jumped immediately, and the rest of the Currituck Banks story is quite apparent today.

Development came quickly to Corolla, NC. Former residents say the change was cataclysmic. Over the next decade, more than 1,500 homes were built on the Currituck Banks between the Dare County line and Corolla village. In 1984 there were 422 homes, but by 1995 there were 1,966 homes. By the year 2000, there were 2,750 homes in that same area. Almost all of these homes are second homes and vacation rentals, sitting empty for most of the year. More than 50 percent of the homes are greater than 5,000 square feet.

All this development quickly filled the empty land on the Currituck Banks, the land that used to provide a nest of isolation to Corolla village. Miraculously, the tiny core of the village has managed to maintain its boundaries and to keep typical Outer Banks development out, though it is a much different place today than it used to be. Many of the historic buildings have been adapted to modern uses, but their character and the sense of village is still intact.

But don’t mistake what you see today for what Corolla village used to be. Many of the buildings you now see are new construction or have been moved to the village from other places. Down the road, the Currituck Beach Lighthouse and the Whalehead mansion have developed modern appeal as tourist attractions. Even so, these attractions and old Corolla village buildings stand in marked contrast to the modern development of the Currituck Outer Banks, helping us to remember that current-day Corolla, NC, does indeed have a past.